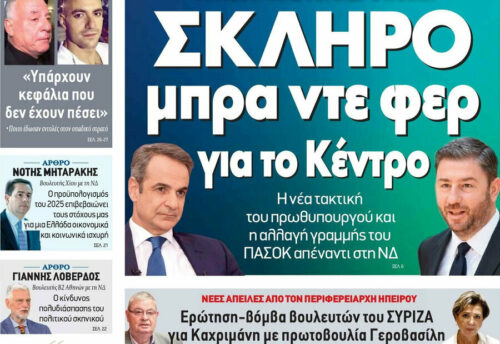

Tsipras’ Aim is to Realign Foreign Policy

In the interview, which took place two days before the referendum vote, Mitarakis explained that while he considered the referendum itself to be illegitimate insofar as what the people would be voting on was twice amended and expired before the vote date, he is voting NAI-YES, because he sees it as a larger question: YES means Greece stays in the euro, and NO means it returns to the drachma.

Mitarakis said that although some feel a NO vote gives Greece more leverage for a better deal, the Tsipras government is not seeking a better deal.

The interview follows:

TNH: Do you think Greeks should vote yes or no to the referendum?

NM: I think it’s a very unfair referendum. First of all, while no one disagrees that the public has to be consulted on major issues, it is the government that has the executive role to make decisions.

This government was elected in January with a very clear mandate to renegotiate the terms of the bailout agreement within the European framework, and now they’re calling for a referendum with exactly the same question.

I do not feel that they do not have their mandate, I cannot understand why they need to renew their mandate.

And it is very unfair, also, because the question being asked is no longer valid. We are asking the people whether they accept the terms of the Institution proposal, but that proposal has been amended twice. Technically, it expired Tuesday night (June 30), as the Greek bailout program was terminated, and just before it expired, Prime Minister Tsipras sent a letter dated June 30 to [European Commission President Jean-Claude] Juncker, accepting 95% of the proposal. So the government is now asking the people to vote no, to an agreement to which in essence, it has said yes, and an agreement that has expired.

So the question is, actually, what is it that we are asking the people to do? Some critics, and I am one of them, believe that the actual question behind the referendum is whether we want to remain within the European framework. Because that is how the whole planet is interpreting this referendum. And I find this referendum to be dishonest, because it is not asking the people what is clearly at stake. A much better question to ask would have been: “are you in favor or against remaining a part of the European Union (EU)?”

The other thing which I think people need to understand is that since January, the economy has frozen. This government has taken a stance against the private sector, investments, and investors, and actually has only focused on the public sector. The cost of the new bailout is multiplying. People have seen a tough proposal by the Institution, a tough proposal by Tsipras – and these proposals are eight times the size of what was needed in December, because the underlying need of the economy has increased.

We [the New Democracy Party] tried very hard in 2012 to change the perception of the Greek economy, focusing on growth, and in 2014 achieved that for the first time since 2007. In 2013 and 2014 we had a positive balance of payments for the first time since 1948. All this was not accomplished without sacrifices. And not without mistakes. Clearly, the people are very right to be angry. They have seen their standard of living go down over the past four years. But instead of talking about the causes, we are talking about the effects. [Is the current government] trying to cure the effects by lying to people? Is austerity bad? Of course it’s bad. But ending austerity [has to mean] producing more. These are the challenges the people have to face, and unfortunately, the government is not being honest with them.

TNH: So your “yes” vote to the referendum, then, is really a yes vote in the broader sense of Greece remaining in the euro.

NP: Yes, exactly. Some people think that a “no” vote means this government will pursue a better deal, but it will not. And I say this now, before the Sunday (July 5) vote.

TNH: Why do you think Tsipras and his government are handling things as they are? What is their goal? And, do you think they will be successful in accomplishing it?

NM: I think the goal in the end has to do with realigning Greek foreign policy away from the West. Let’s look at Greece, at the big picture: Greece after the Second World War was a poor and destroyed economy. The standard of living at the time was not dissimilar to that of our neighbors to the North and to the East. Two generations later – and even after the crisis – Greece ranks among the top developed economies in the world. In that time, we’ve had five different governments, of different political attitude, different constitutional legitimacy – we had democracy and also the military coup.

So, how did Greece manage to achieve a high standard of living, educate its children, and have most of the advantages of a developed country (electricity, water, cars, education, health)? Because we belonged to the West.

That was consistent among all those governments. But now, we are revisiting, questioning, that fundamental dogma that allowed Greeks to emerge from poverty into European prosperity.

Since joining the European Union 35 years ago, Greece has experienced prosperity, security, and stability. But many [Greek] people do not appreciate that. There is a lot of anger, especially among the younger generations, which do not see the same opportunities available that their parents had.

And that is Greece’s biggest challenge: giving the younger generation a sense of hope. But we can only give that hope in an economy driven by the private sector within the European framework. We need to be a pro-market, pro-growth society and economy.

And no one has offered to help Greece economically through this crisis other than its European partners.

TNH: As many of our Greek-American readers – who remember visiting Greece under the drachma in past decades – ask: why it would be so bad for Greece to return to the drachma, at this point, considering they had the drachma all these years before, and things didn’t really seem that bad?

NM: If things were so good under the drachma, so many Greeks wouldn’t have left Greece. If you look at the relative prosperity of Greece, it has grown through its years in the Euro membership. There is always some nostalgia about the past – it’s a natural human tendency, and to remember that “it was better then.” This is a natural bias. The stability and security, the ability to attract investments, to have foreigners bring money into Greece without risk of devaluation, no capital controls regarding the transfer of their wealth in and out of the country.

Greece still imports a lot of goods: technology, cars, food, medicine, energy, and [without the euro], it would take us many, many years to be able to produce these things ourselves, and have them be of high quality and at a competitive price.

Also, it is about security. We live in a very difficult neighborhood of the planet. We are the last border of Europe to the East. Hostilities are not many kilometers away from us, and so we need to remain part of the EU.

TNH: What must the New Democracy Party do to regain the trust of the people, considering they lost significantly in the last election?

NM: We did not lose significantly in the sense that we kept a percentage in the public vote close to that of 2012; simply, our opponents gained momentum from other parties. Politicians are accused of not telling the truth, but when they do tell the truth, they do not become popular. We were honest with people: we imposed taxes, and that made us very unpopular, but that was the only way to meet our economic needs. The only way to pay for salaries, pensions, education, health, and defense. Some critics said we were not tough enough to complete the reforms, and there is some merit to this argument. New Democracy needs to renew its message to the Greek people, about the economic model that Greece needs to follow to exit the crisis and stay out of the crisis. Because it is not about the short-term exit of crisis, but rather not to have a similar crisis again.

TNH: The American media, particularly the conservative media, portray Greece as a country in which the people retire in their 50s, with a full pension, get a month off at Christmas, and sleep in the afternoon. Conservatives in particular point to that as a prime example of the failure of society run by big government (i.e., the Obama Administration). Is that an accurate portrayal, and if not, please clarify what the real picture is.

NM: Greece, unfortunately, has been used as a political example from political people from the left and the right all around the world, trying to make judgments and find commonality with their own problems. According to the European Statistics Office (Eurostat), Greeks are the hardest-working people in Europe. They do not retire that early, and they do work hard. The problem with the Greek economy is that we need more of a private sector, structural pro-growth policies, and more scale (the cost advantage that arises with increased output of a product) in the economy. And so I wouldn’t like Greece to be used as an example by anyone for their own domestic agendas.

TNH: If you were prime minister of Greece right now, what would you do differently from what Tsipras is doing?

NM: The best way to have solved the crisis would have been to prevent it. We would have prevented the crisis [if we were in power.] Greece was about to exit the [bailout] program in February, and was ready to go back to the markets. If we completed the structural reforms, Greece would not have needed another program. We would have been able to produce more, reduce tax rates, and create a positive cycle in the economy.

TNH: Turning to Chios, I noticed that there are a lot of tourists here from Turkey. This is obviously a good sign for Chios’ economy, but does it also enhance Greek Turkish relations as a whole?

NH: I hope it does. There was always a good border relationship between the two countries. Greeks also travel to Turkey. It is good that we are having so many Turks come, but it is negative in the sense that we rely so much on one market (country) for tourism. We need to balance this market [of tourism] better.

TNH: Is there anything else that you would like to share with our readers?

NH: I would like to thank the Greek-American community for being very supportive of the motherland. As there are now newer generations of Greek-Americans, I am very happy to see a lot of them coming to Chios. Please keep on coming, and let us continue to maintain this historical link.